The Elephant in Life of Pi

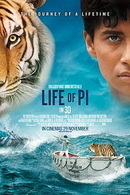

Ang Lee’s Life of Pi was a success in every way, grossing more than $120 million at the box office and receiving an Academy Award for Best Director—something that hadn’t occurred in over 30 years. Quite remarkable for a movie that has as its core a boy and a Bengal tiger alone at sea that can’t help but conjure up Hemingway’s Old Man and his marlin. As with Hemingway’s novel and later film adaptation, Life of Pi is more than just good theater; it ponders the deeper struggles of life.

The Story of Pi

The film begins with Pi Patel, an immigrant from India living in Montreal, being approached by a local writer who has heard that Pi has a story worthy of a book. With very little cajoling, Pi tells his story. His family owned a local zoo, and in his youth Pi takes an interest in the animals, but even more so in religion. His mother’s stories of the Hindu gods are the first to fascinate him, but soon he finds “love through Christ” and “serenity and brotherhood in Islam.” Adding into the mix his father’s rationalism and a bit of Judaism in university, and Pi manages to find something of value in nearly every worldview he explores, even declaring: “Thank you Vishnu, for introducing me to Christ.”

When Pi is 16, his father decides to close the zoo and move his family to Canada. Their passage is to take place with the animals (so that they can be sold upon arrival) on a Japanese freighter. Not long into the journey, the ship confronts a heavy storm and begins to sink. Pi tries to save his family but crew members throw him into a lifeboat, which is soon dislodged from the ship before others can join. As creatures seek survival, Pi eventually finds himself in the lifeboat with an injured zebra, an orangutan that had lost her young, and a spotted hyena. The latter quickly kills the former two until from under the lifeboat’s tarp emerges a Bengal tiger (named Richard Parker) that in turn kills the hyena. Pi is left to survive with Richard Parker. The scene is now set for the long journey of personal survival and guarded friendship that develops between Pi and Parker in 227 dangerous days at sea. As one might imagine, every concept of God and faith are challenged along the way.

Near the end of their strength, the lifeboat eventually reaches the coast of Mexico. Pi stumbles onto the shore and Richard Parker walks into the nearby jungle. Pi expects that before the tiger leaves he will turn and acknowledge him, saying good-bye so to speak, but nothing of the sort happens and Pi weeps even as he is rescued. In the hospital, insurance representatives of the Japanese freighter come to learn of the incident. The story is too unbelievable for their sensibilities and they ask Pi to tell them what “really” happened so a proper story can appear in their report. His accommodating answer, while less fantastic is no less unsettling. Instead of animals in the boat he tells of sharing the lifeboat with his mother, a sailor with a broken leg, and an Indi-hating cook. In this story, the cook kills the sailor for food and later kills Pi’s mother as well. (Think of a hyena killing an injured zebra and soon after an orangutan that has lost her family.) In return Pi kills the cook mirroring the action of Richard Parker towards the hyena. Or was it that the other way around: did the story of Richard Parker and the animals in the lifeboat mirror the “real” story of a human struggle for life? This is the question that the writer is left to ponder and any viewer of the film as well.

Pi’s Elephant

Amidst this odd, yet beautifully filmed story (or shall we say two stories?), Pi’s journey has some seemingly good results. He recognizes that his survival cannot be attributed to personal grit and determination: “Even when God seemed to have abandoned me, he was watching. Even when he seemed indifferent to my suffering, he was watching and when I was beyond all hope of saving.” Such a perspective of God brings him to a place of surrender reluctant as it might be: “I lost my family! I lost everything! I surrender! What more do you want?” Furthermore, in the end, he learns the great value of saying good-byes: “I suppose in the end the whole of life is an act of letting go, but what always hurts the most is not taking a moment to say good-bye.” And, of course, Pi has also learned that life on earth is full of suffering.

It is not uncommon for Eastern philosophers to liken religion to that of blind men feeling an elephant. No one religion is said to contain the whole truth. Just as blind men come to different conclusion based on feeling a trunk, a leg, or a tusk, so human religions have come to different conclusions based on their own perspectives and experience. But no one is able to see the whole, so goes the parable, and neither can we when it comes to God. Of course, the whole illustration is rather problematic because one must stand in the position of seeing the whole elephant in order for it to make sense, something which the very parable says is not possible.

In Life of Pi, one is compelled to admit that Pi has rightly identified some parts of the elephant even if he has missed on others. He has discerned that God is attending to our very life even in our most desperate hours, that suffering is a real part of the world and should bring us to a place of surrender, and that our desire for relationships (which is based in the image of God) means that the end of relationships is painful and worthy of gracious good-byes. But despite these inklings of truth, Pi’s ultimate declaration regarding the larger “elephant” is rather disconcerting.

After laying out the two stories to the hopeful writer, Pi sets up the writer (and the viewer) to discover what he has taken from his whole experience.

For Pi then, what is important is not which story is true, but rather which story is to be preferred given the circumstances. He has endured great pain and suffering. Two stories are available to explain what happened. For him, and the writer agrees, one is to be preferred. This preference, however, is not based on reality but rather on what Pi finds helpful in coping with his own personal history. His conclusion is that this is what all stories about God are about. Religious ideas are not things that can be shown to be true or not; they are simply means by which we cope with the experiences that come our way. That is the “elephant” that people often fail to see, so implies Pi.

A Christian Response

As a Christian, I find Pi’s conclusion unsatisfying. I don’t want to cope with life through preferential stories that make me feel better. Perhaps this would be appropriate if there was no God, or if God did not reveal himself in the world. In that case, I could pick stories like I pick comfort food. But in light of a real God who has shown himself in human history to be compassionate and merciful, and in light of a God who promises to right all wrong and wipe away every tear and has made that possible by his own coming in time and space, I find no need to resort to self-crafted stories. The apostle Paul wrote if Christ has not been raised, the Christian faith is futile and we are stuck in our sins (1 Cor 15:17). Paul did not see any virtue in holding to a religion that was merely a story made up to help the early Christians cope. For him, Christianity was only worth preferring if it was based in solid historical evidence. For Pi though truth is not important. He knew which of the stories was true (or if neither was true). But without a proper understanding of the Christian God and His accompanying redemption and hope, truth was shuttled away in fictional stories of solace.

Unfortunately, Pi’s conclusion is not uncommon today. Religion is seen as something which people must take only by faith. It is something that cannot be substantiated we are told. It is a matter of the heart. And any religion is as good as another if it works for you. At best, religions are but parts of a larger elephant that has no basis in reality. Again, such a position might be warranted if God had not definitively shown up in the world or if finding something that temporarily soothes our conscience or our sorrows is the best we can do. But we can do better than that, because God has done better than that. He has shown us the “elephant” for what it really is (or who He really is) and in that light fanciful stories of preference will fall forever flat even if they are spun in the beautifully told Life of Pi.

©2013 John Hopper

The Story of Pi

The film begins with Pi Patel, an immigrant from India living in Montreal, being approached by a local writer who has heard that Pi has a story worthy of a book. With very little cajoling, Pi tells his story. His family owned a local zoo, and in his youth Pi takes an interest in the animals, but even more so in religion. His mother’s stories of the Hindu gods are the first to fascinate him, but soon he finds “love through Christ” and “serenity and brotherhood in Islam.” Adding into the mix his father’s rationalism and a bit of Judaism in university, and Pi manages to find something of value in nearly every worldview he explores, even declaring: “Thank you Vishnu, for introducing me to Christ.”

When Pi is 16, his father decides to close the zoo and move his family to Canada. Their passage is to take place with the animals (so that they can be sold upon arrival) on a Japanese freighter. Not long into the journey, the ship confronts a heavy storm and begins to sink. Pi tries to save his family but crew members throw him into a lifeboat, which is soon dislodged from the ship before others can join. As creatures seek survival, Pi eventually finds himself in the lifeboat with an injured zebra, an orangutan that had lost her young, and a spotted hyena. The latter quickly kills the former two until from under the lifeboat’s tarp emerges a Bengal tiger (named Richard Parker) that in turn kills the hyena. Pi is left to survive with Richard Parker. The scene is now set for the long journey of personal survival and guarded friendship that develops between Pi and Parker in 227 dangerous days at sea. As one might imagine, every concept of God and faith are challenged along the way.

Near the end of their strength, the lifeboat eventually reaches the coast of Mexico. Pi stumbles onto the shore and Richard Parker walks into the nearby jungle. Pi expects that before the tiger leaves he will turn and acknowledge him, saying good-bye so to speak, but nothing of the sort happens and Pi weeps even as he is rescued. In the hospital, insurance representatives of the Japanese freighter come to learn of the incident. The story is too unbelievable for their sensibilities and they ask Pi to tell them what “really” happened so a proper story can appear in their report. His accommodating answer, while less fantastic is no less unsettling. Instead of animals in the boat he tells of sharing the lifeboat with his mother, a sailor with a broken leg, and an Indi-hating cook. In this story, the cook kills the sailor for food and later kills Pi’s mother as well. (Think of a hyena killing an injured zebra and soon after an orangutan that has lost her family.) In return Pi kills the cook mirroring the action of Richard Parker towards the hyena. Or was it that the other way around: did the story of Richard Parker and the animals in the lifeboat mirror the “real” story of a human struggle for life? This is the question that the writer is left to ponder and any viewer of the film as well.

Pi’s Elephant

Amidst this odd, yet beautifully filmed story (or shall we say two stories?), Pi’s journey has some seemingly good results. He recognizes that his survival cannot be attributed to personal grit and determination: “Even when God seemed to have abandoned me, he was watching. Even when he seemed indifferent to my suffering, he was watching and when I was beyond all hope of saving.” Such a perspective of God brings him to a place of surrender reluctant as it might be: “I lost my family! I lost everything! I surrender! What more do you want?” Furthermore, in the end, he learns the great value of saying good-byes: “I suppose in the end the whole of life is an act of letting go, but what always hurts the most is not taking a moment to say good-bye.” And, of course, Pi has also learned that life on earth is full of suffering.

It is not uncommon for Eastern philosophers to liken religion to that of blind men feeling an elephant. No one religion is said to contain the whole truth. Just as blind men come to different conclusion based on feeling a trunk, a leg, or a tusk, so human religions have come to different conclusions based on their own perspectives and experience. But no one is able to see the whole, so goes the parable, and neither can we when it comes to God. Of course, the whole illustration is rather problematic because one must stand in the position of seeing the whole elephant in order for it to make sense, something which the very parable says is not possible.

In Life of Pi, one is compelled to admit that Pi has rightly identified some parts of the elephant even if he has missed on others. He has discerned that God is attending to our very life even in our most desperate hours, that suffering is a real part of the world and should bring us to a place of surrender, and that our desire for relationships (which is based in the image of God) means that the end of relationships is painful and worthy of gracious good-byes. But despite these inklings of truth, Pi’s ultimate declaration regarding the larger “elephant” is rather disconcerting.

After laying out the two stories to the hopeful writer, Pi sets up the writer (and the viewer) to discover what he has taken from his whole experience.

- Adult Pi: Can I ask you something? I’ve told you two stories about what happened out on the ocean. Neither explains what caused the sinking of the ship, and no one can prove which story is true and which is not. In both stories, the ship sinks, my family dies, and I suffer.

- Writer: True.

- Adult Pi: So which story do you prefer?

- Writer: The one with the tiger. That’s the better story.

- Adult Pi: Thank you. And so it goes with God.

For Pi then, what is important is not which story is true, but rather which story is to be preferred given the circumstances. He has endured great pain and suffering. Two stories are available to explain what happened. For him, and the writer agrees, one is to be preferred. This preference, however, is not based on reality but rather on what Pi finds helpful in coping with his own personal history. His conclusion is that this is what all stories about God are about. Religious ideas are not things that can be shown to be true or not; they are simply means by which we cope with the experiences that come our way. That is the “elephant” that people often fail to see, so implies Pi.

A Christian Response

As a Christian, I find Pi’s conclusion unsatisfying. I don’t want to cope with life through preferential stories that make me feel better. Perhaps this would be appropriate if there was no God, or if God did not reveal himself in the world. In that case, I could pick stories like I pick comfort food. But in light of a real God who has shown himself in human history to be compassionate and merciful, and in light of a God who promises to right all wrong and wipe away every tear and has made that possible by his own coming in time and space, I find no need to resort to self-crafted stories. The apostle Paul wrote if Christ has not been raised, the Christian faith is futile and we are stuck in our sins (1 Cor 15:17). Paul did not see any virtue in holding to a religion that was merely a story made up to help the early Christians cope. For him, Christianity was only worth preferring if it was based in solid historical evidence. For Pi though truth is not important. He knew which of the stories was true (or if neither was true). But without a proper understanding of the Christian God and His accompanying redemption and hope, truth was shuttled away in fictional stories of solace.

Unfortunately, Pi’s conclusion is not uncommon today. Religion is seen as something which people must take only by faith. It is something that cannot be substantiated we are told. It is a matter of the heart. And any religion is as good as another if it works for you. At best, religions are but parts of a larger elephant that has no basis in reality. Again, such a position might be warranted if God had not definitively shown up in the world or if finding something that temporarily soothes our conscience or our sorrows is the best we can do. But we can do better than that, because God has done better than that. He has shown us the “elephant” for what it really is (or who He really is) and in that light fanciful stories of preference will fall forever flat even if they are spun in the beautifully told Life of Pi.

©2013 John Hopper